They Grow Up So Fast

But, like, how fast are these Wizards going to grow?

There’s an 2006 local news segment of a 17 year old Russell Westbrook that I come back to every couple of years. He dunks and passes and tries to mean mug for the camera through the 10 minute (!) segment. But he’s clearly a kid. At one point he talks about praying for his family and it’s—and I say this objectively and after crunching the numbers—just incredibly cute and wholesome. Fans (and haters) of the former Wizards star, will recognize the outline of the 2016 -17 MVP in the clip, but it is also clear that he was years away from truly being an NBA player. But how long does that take? What’s the growth path from scrawny kid to NBA adult?

It is an awkward topic, admittedly, or at least can be. We’re talking about peoples’ bodies, bodies that are constantly being judged, and, more often than not, bodies in a country that has put a literal value on the worth of those bodies and then treated them as worth less. It should go without saying, but I will: every body is beautiful and deserving of love and also a kind of disgusting collection of bile and guts and farts and mysteries, so let’s celebrate and respect that.1 And yet, if you’ve watched the past two weeks of Wizards games, it is hard not to see.

AJ Johnson getting pushed around by Jaylen Clark, Kyshawn George struggling against Aaron Gordon in the paint, Sabonis needling Sarr further and further from the basket until Sarr attempts a questionable midrange shot. This isn’t a judgement on who the Wizards are, but given that this current team is essentially speculative, it does make one (I don’t know why I’m being precious here, it makes me) wonder if these are the guys as they will always be, or if, like 19 and 20 year olds everywhere, there’s still more growing in store. It is unlikely many of the players on the current roster will even be around in three years, but for the ones who are able to stick it out in DC, are they going to find ways to work in the bodies they have or will they become the guys bullying people in the paint?

Most people think about Giannis, or the handful of other young guys who enter as rookies in the mid-to-upper six foot range and by season three are closer to seven feet, but looking at data from the past 25 years shows that this is actually pretty rare. Weight, on the other hand, does change. This is partly because weight is correlated with muscle mass. It is tough to get taller—many of us know the genetic ceiling all too well—but getting stronger is, at least to some extent, within a player’s control.

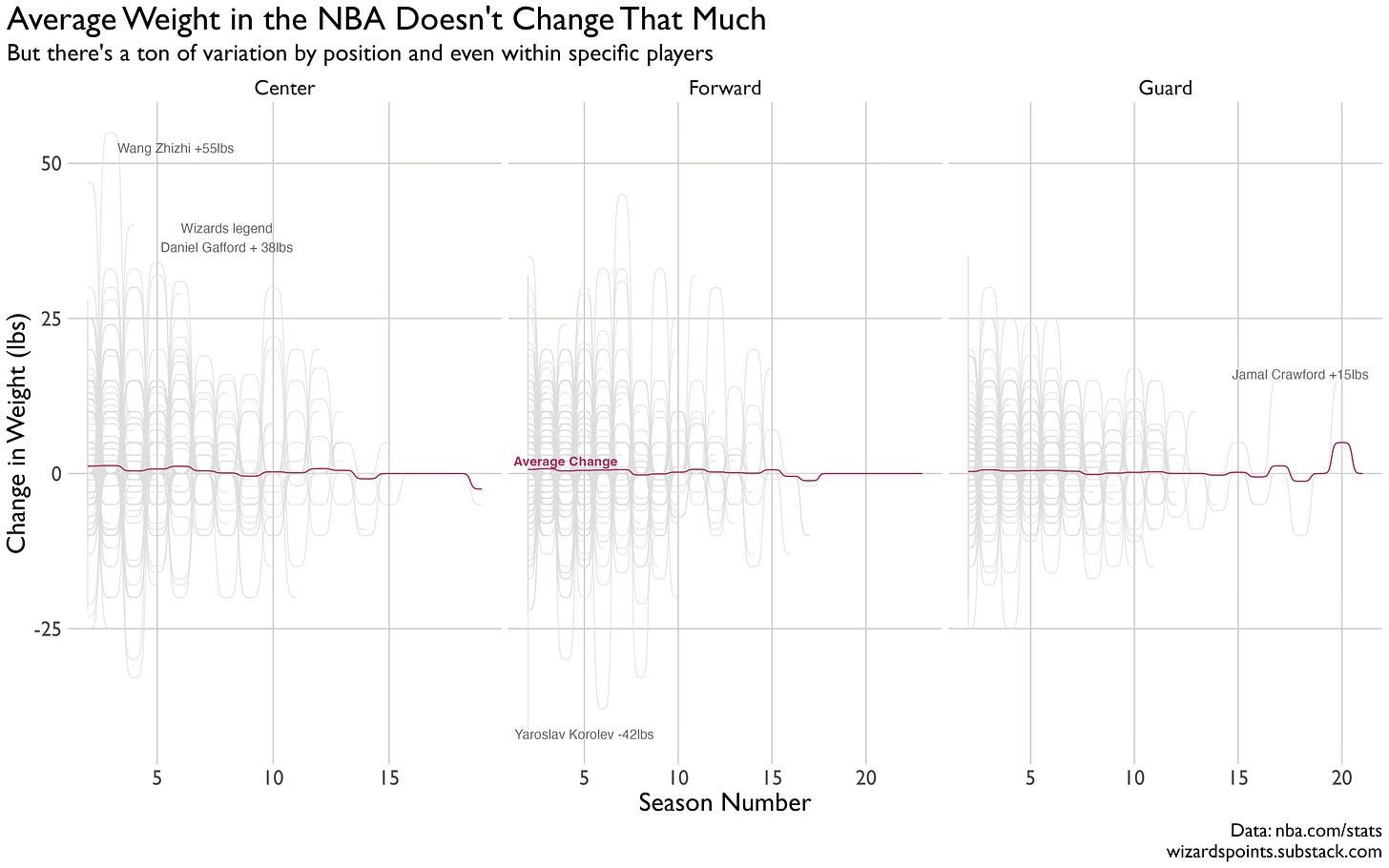

As we can see in the figure, the overall change in average weight doesn’t move that much season-to-season. Yet, some players see huge increases and decreases. Our old pal Daniel Gafford got traded to the Dallas Mavericks and suddenly had shoulders you could see from the upper deck. Similarly, Deni Avidja went from being listed at 210 pounds in his last season in DC to 240 when he started the 2024-25 season in Portland (weirdly, Deni is one of the few players who lost height, losing an inch between 24/25 and 25/26).

Given how much variation there is in the data, simply looking at averages and assuming some sort of straight line in weight and seasons played might obscure how players actually grow. There is also the fact that weight might be misreported or simply measured with some error. Maybe the scale being used wasn’t quite calibrated the right way, maybe a guy had a big lunch. Whatever the case, it’s plausible that you could weigh yourself three times in a week and get three different measurements.

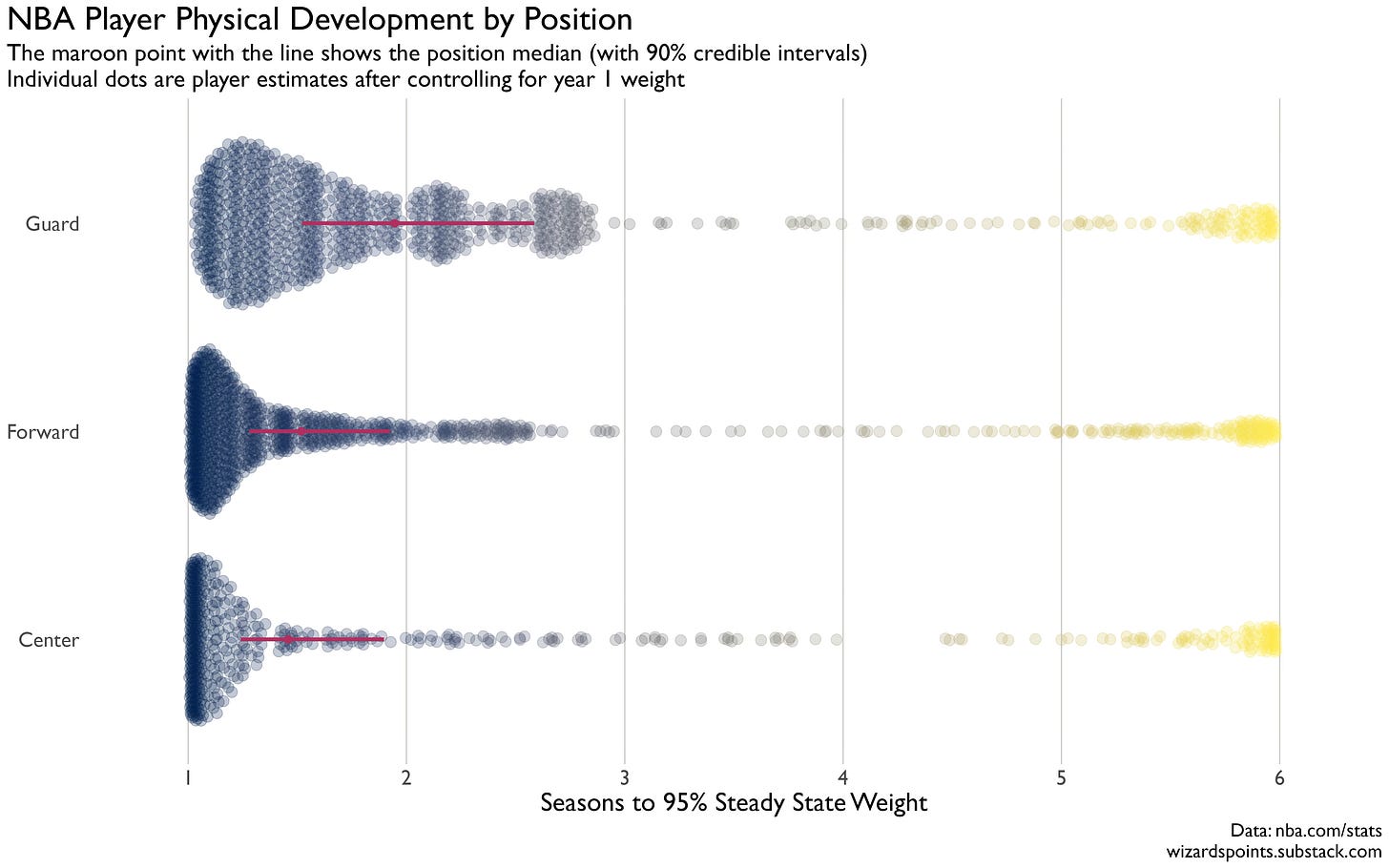

If you have ever had a small child, or known someone who has a small child, you have likely encountered a growth curve to understand whether or not a child is developing within some age appropriate range. Using the NBA’s weight data, I basically reconstructed this idea using each player’s first season weight and then tracking each subsequent season to understand the time it takes to get to 95 percent of their final or steady state weight, i.e., the point after which they kind of level off. Some players get there quickly (1-2 seasons), while others take longer (3-5 seasons).

Rather than just averaging across players, though, which would assume some sort of straight progression, we use a statistical model that borrows information across similar players so that guards inform our understanding of other guards, centers inform other centers. This is important in cases like Yaroslav Korolev where there isn’t a ton of data on an individual level and the changes are extreme.

The model assumes weight follows an identifiable curve: players start at their rookie weight and approach their mature weight over time (if we’re getting technical, this is called asymptotic growth). This allows us to get a sense of some actionable overall numbers, as well as individual estimates for where a player is in their growth journey.2

As shown below, the median time to hit steady state is around two seasons for guards, while forwards and centers hit their steady state weight about mid-way through their second season. This kind of tracks with the types of players who get drafted in these positions: a 19 year old guard tends to be a skinny kid who is quick on his feet, while big men on the team are often entering the NBA having played in the paint in college or abroad, having to tough it out under the basket, and need to continue building strength to get minutes.

If you just look at raw numbers and average across players, you get slightly higher results because there are a handful of guys, like Jamal Crawford, who play a ton of seasons and who have higher than average variation in their weight. For guards, their overall raw average is around three seasons, while centers and forwards level off at season 2.5. But again, the results above from the model help account for the fact that growth isn’t linear and hitting a steady state depends on where you start, when you play, and for how long.

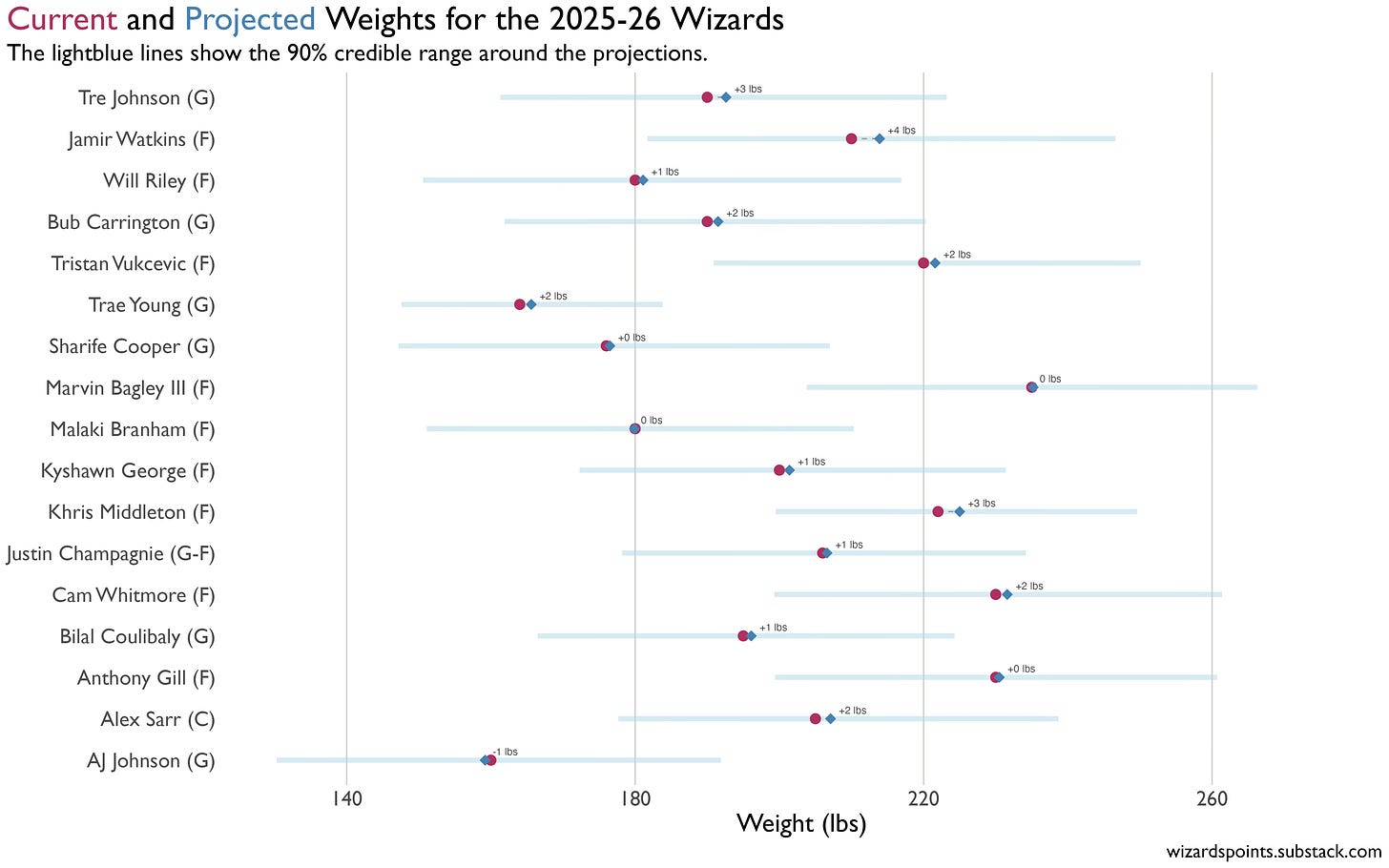

These results—that guys are who they are by their third season and more often by their second—are both promising and a little terrifying. The Wizards are now solidly in year three of their rebuild, with a young core of second-year players. It has been so great to see Alex Sarr suddenly split defenders or pivot in the paint for a fadeaway. I have no doubt that rookie Tre Johnson’s heart and grit will take him far. It is also clear that from the most elite stars to the workaday players who stick around, building strength and gaining weight is critical. The eye test says the Wizards are getting stronger. It also says they have a ways to go.

I plugged the current roster into the model to project where the guys might go and see who is likely still growing. Based on the number of seasons to get to each player’s projected steady state weight, Tre Johnson, Jamir Watkins, Will Riley, Alex Sarr, and Bub Carrington are projected to continue gaining weight in a way that the model suggests is outside of season-to-season variance. This is not too surprising given how young those players are. The model suggests that Tre Johnson is 1.6 seasons away from hitting 95% of his steady state weight, while Will Riley and Bub will be there next season. Notably, the model doesn’t quite know how to handle Sarr. It suggests that he is likely only about halfway through his development process, but also that he likely won’t gain that much more weight. This is sort of contradictory to me and not super helpful. Still, if most guys are who they are by season three, Sarr is nearly there. he’s leading the league in blocks per game. He’s developing an inside game. I don’t feel too worried that this model is kind of all over the place with him.

Zion gains weight and loses it. Lebron loses weight and then gains it. Guys check into games looking like they got into an argument with their barber. The body is on full display in the NBA in a way that belies how vulnerable these 20-something players are when they step onto the court. The main benefit—maybe the only benefit—of watching a team like the Wizards is getting to observe players develop. You get to see the small steps and the big leaps. You watch Will Riley get rejected by the rim one game and then move through space for a dunk a few games later. But it’s impossible not to see how much room there is to grow. I come back to the Russ clip not only to see an innocent moment captured in time, but to see how much of the superstar was already there.

I just got over norovirus, so the multitudes that the body contains has never felt more real.

Just to get technical here, I fit a Bayesian hierarchical growth-curve model in which each player’s weight follows a smooth rise and then levels off, with position-level priors and player-level deviations for rookie weight, total weight gain, and time to maturity. All player parameters are partially pooled by position. The time-to-maturity parameter is constrained to a plausible range using informed priors to stabilize estimates and avoid implausible growth patterns. The model overall does a good job, but there are some weird results too. For example, it doesn’t quite handle AJ Johnson all that well in my opinion. AJ put on a decent amount of muscle between last year and this year (though he’s still pretty light), but the model treats this less as a trend and more as weight that will revert closer to his rookie level. As always, code is on GitHub here.